Damni Kain

Caste-based discrimination takes place not only when caste-based atrocities are committed, but due to the very existence of the caste system in India, where people are born “unequal” (to borrow Dr BR Ambedkar’s words). It is a hierarchical society where ascriptive identities dictate one’s social, economic, and political positions, and uses violation of rights as its primary tool to maintain the system.

Caste-based discrimination takes place not only when caste-based atrocities are committed, but due to the very existence of the caste system in India, where people are born “unequal” (to borrow Dr BR Ambedkar’s words). It is a hierarchical society where ascriptive identities dictate one’s social, economic, and political positions, and uses violation of rights as its primary tool to maintain the system.

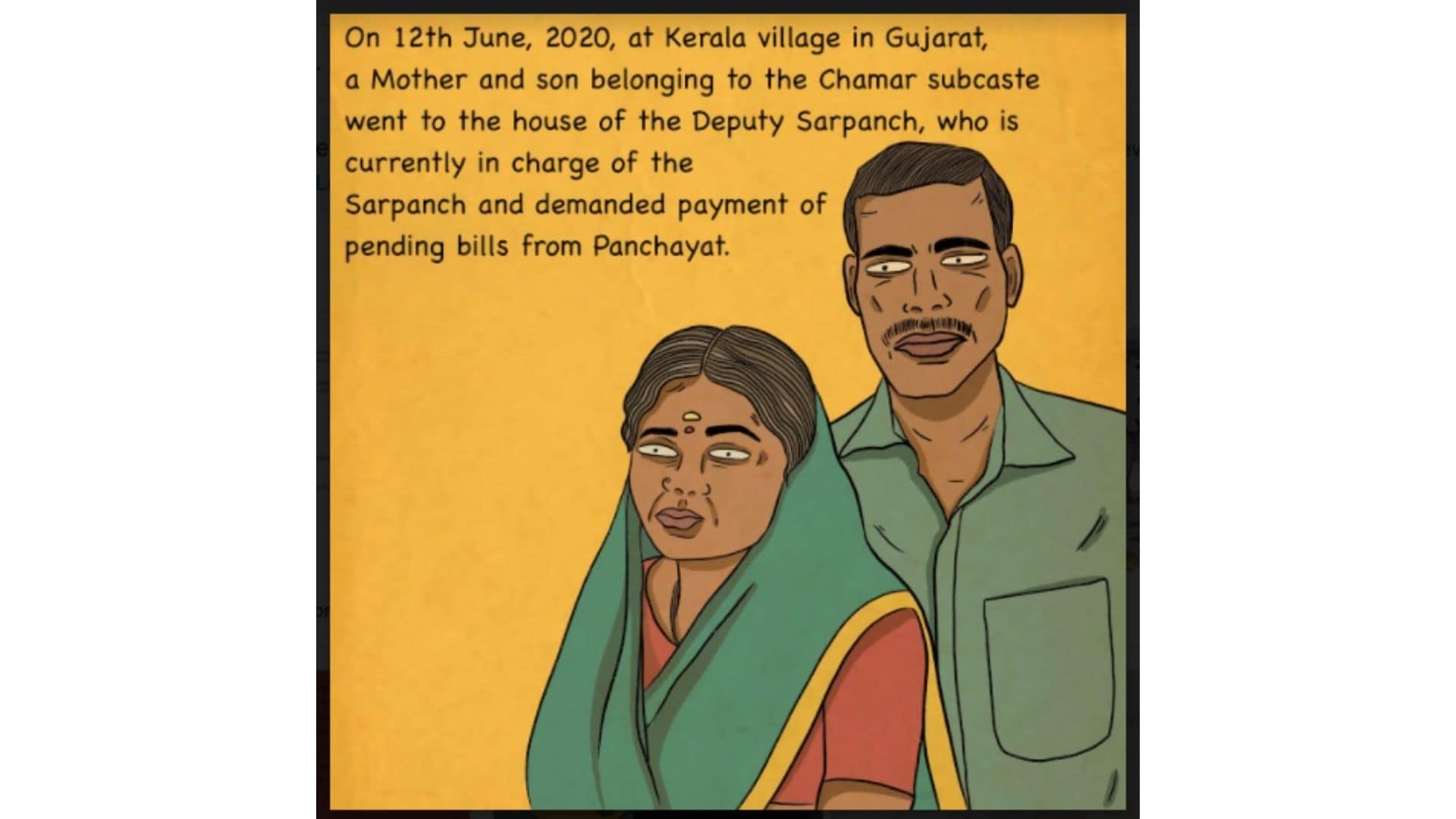

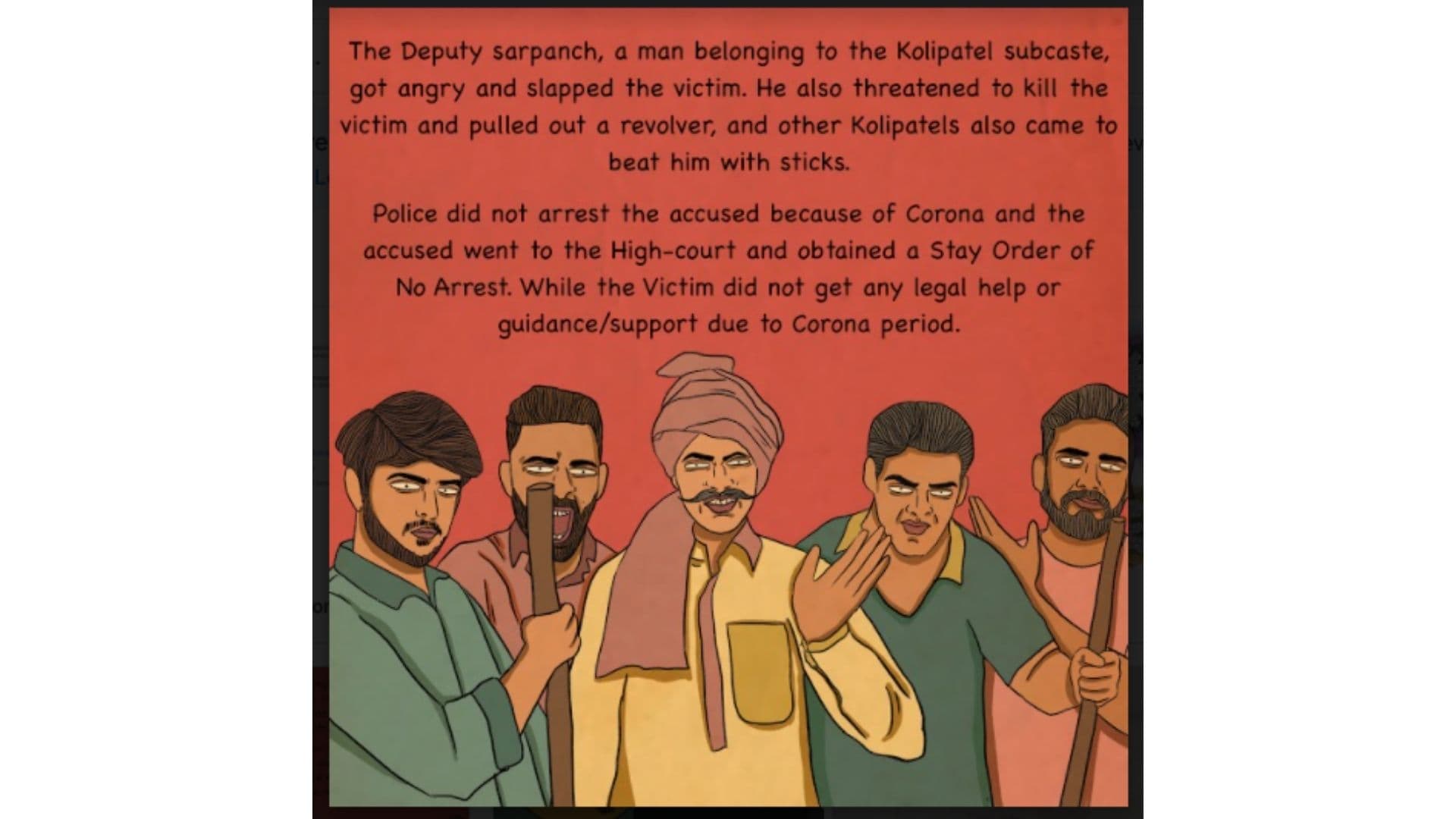

Talking about caste-based atrocities amidst the COVID-19 lockdown does not mean that said atrocities did not exist prior to it; instead, it highlights how the lockdown has pushed the already vulnerable to extreme edges of marginalisation on several fronts. The lockdown has been witness to a specific set of repeated patterns through which the dominant caste-based nexus has been operating to deny fundamental rights to Dalits. Many such cases came to the limelight after being widely shared and discussed on social media. Protests and campaigns were staged as an aftermath.

#LockdownCasteAtrocities is one such social media campaign by Dalit Human Rights Defenders Network (DHRDNet) in collaboration with Public Bolti that aims to share “stories of pain, plight and struggle of Dalits” that need visibility and solidarity both at the national and international levels, since Dalit rights need to be addressed as human rights.

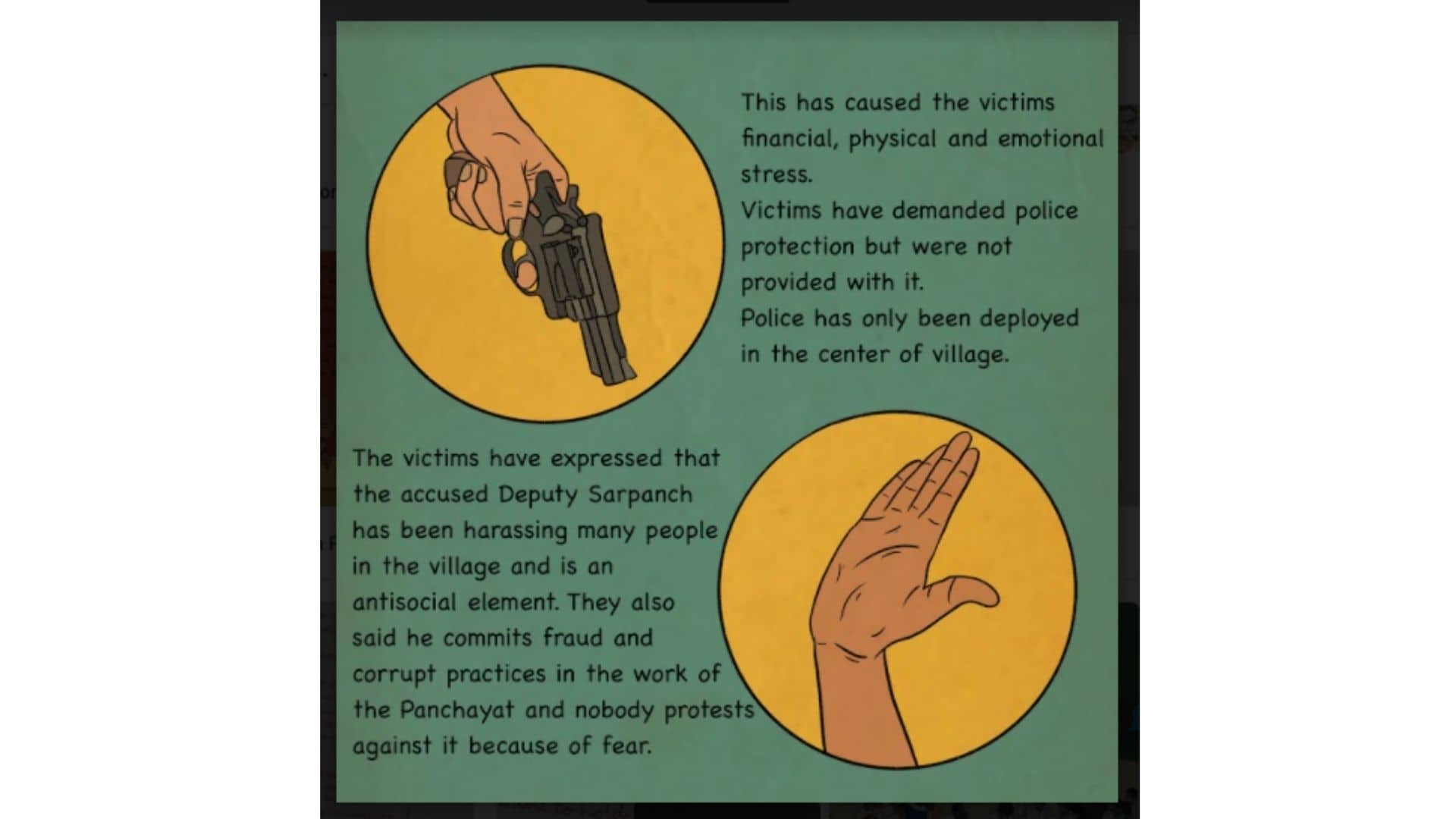

The COVID-19 lockdown has emerged as a lockdown of not just justice, but rights as well. Campaign Director Manjula Pradeep sheds light on how the police and the administration have been delaying the performance of their duties using the pandemic as an excuse. She listed several challenges amidst the lockdown and said, “The first challenge was to reach out to the affected Dalits physically, which was not possible due to the lockdown. The other challenge was lack of support of the administration and the local police who were posted to ensure that the lockdown rules are followed. Those DHRDs who tried to provide help to the affected Dalits were targeted not only by the police but also by the dominant castes. False cases were registered against some of the DHRDs and some of the DHRDs were attacked, which resulted in serious injuries or deaths.”

DHRDNet is a coalition of more than 1,000 Dalit human rights defenders across India, who follow a “rights-based approach” to fight caste-based discrimination, employing a well-structured plan of action. The organisation first engages in capacity building programmes for Dalit human rights defenders, especially women. The skills gained through this programme are then directed to develop legal assistance and monitoring programmes, which are in turn used to expand dialogue both at the level of society and the government.

One of the several achievements of DHRDNet is that the organisation has successfully provided access to justice through legal assistance and information dissemination to over one lakh Dalits, with half of them being women. Several campaigns and events have been launched by DHRDNet on caste-based atrocities, Dalit youth and rights of Dalits.

On the other hand, Public Bolti is a citizen journalism and advocacy platform which is working together with DHRDNet to mainly focus on social media.

A campaign cherishing dignity

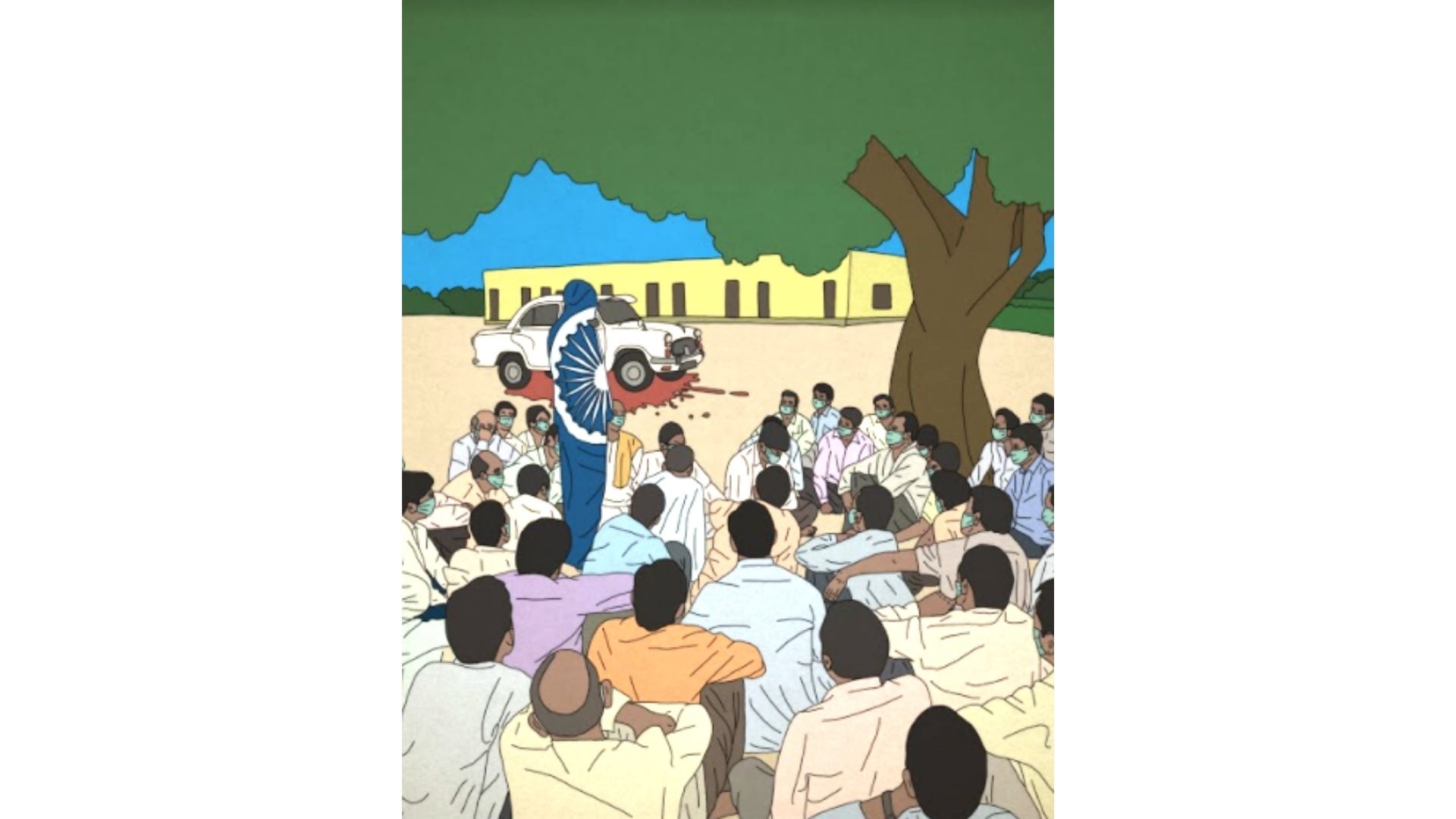

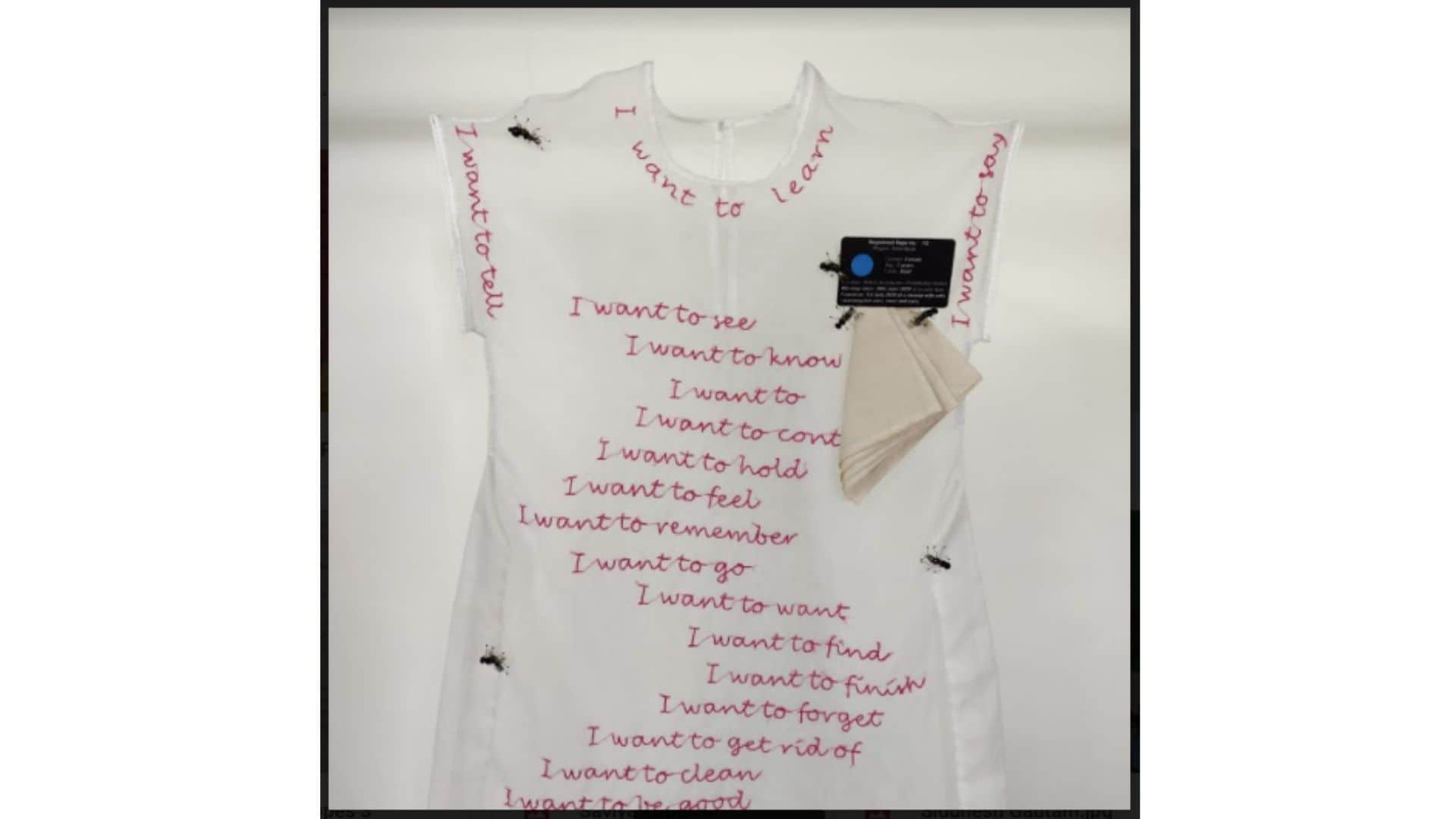

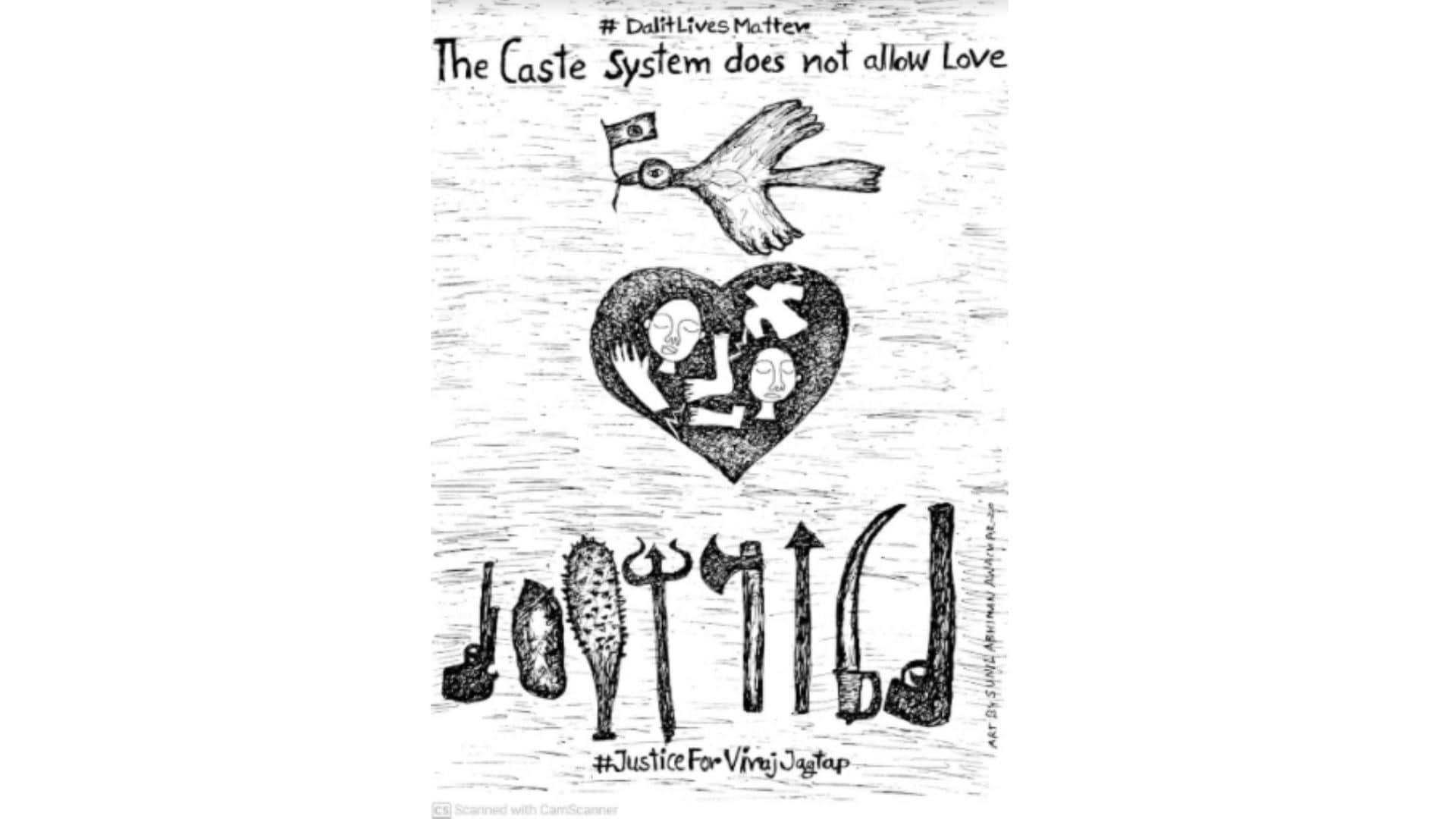

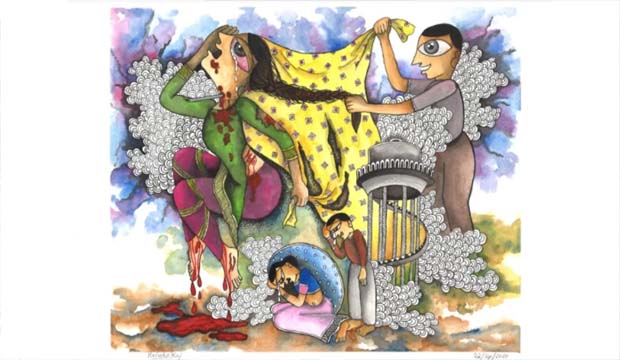

#LockdownCasteAtrocities is a multi-dimensional campaign that brings forth a combination of resistance and awareness, while upholding the dignity of the victim/survivor. To highlight the cases, the campaign features 30 artists from Bahujan communities to present 30 cases over 30 days. The mediums are as diverse as rap songs to illustrations and poetry. Furthermore, the campaign engages in conversations on various aspects related to caste-based atrocities through sessions with on-ground experts, media and various ‘Call to Action steps for allies.

Dissemination of information is a key area of focus. Volunteers of the campaign are preparing a report on caste crimes that took place during the pandemic in five Indian states — Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Maharashtra. The report will be released by the first week of November 2020.

Along with this, the campaign will file a petition to the United Nations’ organisations, posing the request to “institutionalise regular reporting and effective dialogue on the elimination of discrimination based on caste and analogous forms of inherited status.”

The second petition presents a detailed list of recommendations for political executives (mainly MPs and MLAs) to prevent and provide redressal for caste crimes in their individual states.

The campaign has several key highlights, ranging from politics to pedagogy, art to awareness and representation to rights.

Art and politics

The campaign rightly represents art as a political expression in the anti-caste discourse. Illustrator Priyanka Paul, who participated in the campaign, highlights the inter-linkages between art, politics and social media, as she argues, “Art has been an important mode of political expression since time immemorial, and now more than ever, in the era of social media where ‘aesthetics’ are so focussed upon. Politics is so much about how we see and perceive, and visual mediums have immense power to influence that. I have also always believed that the purpose of art is for it to inform, if not educate, and for it to bear true testament to its time of creation. Which is why it is important to be aware of the media and art you consume, and inquire who it is made by, why it has been made, and what it has been made for. Art made simply to please people’s eyes is an injustice to its immense power and potential, according to Malvika Raj, who sees the Dalit Art Movement as a “voice and expression of a group of artists, practicing varying forms of art in order to strongly dismantle the brahmanical, fascist and patriarchal culture.”

The importance of pedagogy

Much of the sensitisation for equality requires a process of “unlearning”. Knowledge production in society reflects the socio-economic cleavages on which it is constructed. Mainstream course structures in Indian schools absorb much of brahmanical ideas and concepts, which needs to be replaced with alternative models of learning. Pedagogy plays an important role in the anti-caste struggle that aims to revamp Indian society from the very roots. Unlike conventional awareness campaigns focusing on adults alone, #LockdownCasteAtrocities is unique as it also curates a list of anti-caste books for children and the sites from where one could access them. The list includes books like Turning the Pot, Tilling the Land by Kancha Ilaiah and Durgabai Vyam, and The Adventures of Young Ambedkar by Devyani Khobragade.

Representation

The question of who presents the case becomes important for representation as well, urging a better analysis of the situation. In this regard, the campaign has made sure that all the 30 artists are from marginalised communities. Shrujana, a volunteer at Public Bolti and #LockdownCasteAtrocities opposes triggering and tokenistic representations in mainstream media, and adds, “Caste atrocities should be the talking point on primetime television, or even OTT platforms. But mainstream media in India elbows out anti-caste news, issues, and narratives. At most, they cover only the extremely gruesome cases, that too by trampling upon the dignity of the individual concerned.”

Pandemic and police brutality

The campaign lists down data from official authorities like the National Crime Records Bureau that was released recently as a marker to see how the assumed ‘protectors’ have played a dominant role in assaulting Dalits, and extending impunity towards perpetrators from so-called “upper-caste” backgrounds. The official data highlighted an increase in crime against Dalits and specifically Dalit women over successive years. This data though cannot be considered as completely reliable since many cases of atrocities against Dalits are either not registered or registered in less severe sections to provide easy escape from penalty for alleged culprits. Manjula Pradeep highlights how the aftermath of registering crimes against Dalits has in many cases lead to their social ostracisation, physical attacks, harassment, and even murders in the wake of no police protection, or even the registering of counter cases by the accused with the police.

‘Know your rights’

The campaign is not limited to a one-way approach of merely mentioning cases of atrocities, but also highlights relevant rights both as a preventive and redressal measures. Broadly, the ‘know your rights’ section is divided into several sub-sections of constitutional rights, legal rights, property rights, voting and electoral rights, and a list of actions considered legally as ‘crime’ against Dalits.

‘Constitutional Rights’ mentioned in the campaign detail articles like Article 15 (equality of status and opportunity) and Article 46 (educational and economic upliftment of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes).

Several Acts such as The Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955, The Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, and the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993 are discussed at length under the ‘Legal Rights’ section.

‘Property, Voting and Electoral Rights’ reiterates civil and political rights, ensuring equality as granted in the Constitution for Dalits. This section lists fines and punishments on infringement of said rights.

In the age of social media, campaigns like #LockdownCasteAtrocities can help gain momentum in the fight against inequality and caste-based discrimination in India. It not only serves to raise one’s voice, but also to build solidarities across the globe.

Courtesy Firstpost